Leaving the economic crisis aside, the European Union is risking its own future on a different front. The secessionist party Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (Alliance Neo-Flamenca-NVA) recently swept Belgian municipal elections. In Edinburgh British Prime Minister David Cameron and Scottish premier Alex Salmond have reached an agreement so in 2014 Scotland will vote for independence. And on November 25 the Catalans will go to the polls to elect a Parliament that promises the right to self-determination. And these are only the more advanced processes.

For some European leaders it is not easy to discuss greater European integration in Brussels while in their States the economic crisis is feeding extremism, populism and nationalism.

Worried about this situation the head of Italian Government, Mario Monti, asked their European counterparts at the last meeting in Brussels to organize an informal meeting of Heads of State and Government. Greece’s Premier Antonis Samaras talked about the Greek experience with the racist party Aurora Dorada, which currently has 18 seats in Parliament. And Belgian Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo pointed out that there is an independence party–the NVA–that actually wins elections in his country. The amalgam is dangerous.

Can we compare pro independence democratic parties in Flanders, Catalonia or Scotland with those extreme right formations such as Aurora Dorada, the National Front in France, the Freedom Party in Holland or the Hungarian Jobbik? Of course not. But Belgian Prime Minister added something else in response to this question: “They aren’t the same thing,” he said, “but we try to reinforce European integration and those parties, even if they are different, are centrifugal whereas we are centripetal.”

Mario Monti wants to start a “philosophical debate” with the aim of reducing “centrifugal risks” in the bosom of the European Union. It is also in his interest that this works out since Italy has the Northern League and the South Tyrol.

SCOTLAND

English and Scots have always had a love-hate relationship. Before both countries became one in 1707, historians estimate that they clashed in at least 56 great battles. In 2011 the Scottish National Party (SNP) won an absolute majority in the local parliamentary elections and with that victory came the final battle for independence.

After months of negotiations, a final referendum on the future of the five million Scots was set for 2014. Scotland is poorer than England although it is Europe’s largest oil producer, and it has strong banking, tourism and naval sectors. Its future permanence in the EU is therefore particularly important.

Now it has been reported that the Chief Minister Alex Salmond lied saying that he had favourable reports to EU integration reports if the ‘yes’ option won in 2014 referendum. Perhaps his intention was to ask three questions in the referendum: independence, no change of situation at all, or an intermediate solution. However British Prime Minister finally forced a clear question with an unequivocal result: independence yes or no. London has dismissed half-way measures: the SNP wants an own country that still belongs to the British Crown and the EU, and that uses the pound as a currency. Cameron has warned that Isabel II and the pound will not be included if they leave.

This vote will be a life or death matter for nationalists, that also exist in Wales. The British Government hopes that a resounding ‘No’ will end up with pro-independence parties losing all grounds for their complaining.

FLANDERS

NVA supporters will sweep, more than likely, in 2014. This will allow them to block the State even stronger than in 2011’s nightmare of 2011 when the country got the world record of a state without a government. Last month, this party won municipal elections in the non French-speaking half of the country.

“We have reached a point of no return. We have chosen change and we will continue on that path,” said the separatist Bart de Wever shortly after becoming mayor of the first Flemish city, Antwerp. They say they are tired of subsidizing the French-speaking Walloons. There is also an ideological breakthrough: while the Walloons are left-wing supporters, the Flemings vote right. They are actually more likely to achieve their goals. Unlike Catalonia or Scotland, Flanders is richer than all the rest of Belgium and… it is more populated.

They are in the majority, which is an important fact in a democracy. They are the only ones who can aspire to organize their own State as they want because they occupy key positions in the country and have parliamentary majorities to achieve their goals. This not the same thing as being independent. Especially because they know that if they come out of the EU they’d lose more than they’d had won.

Their goal is to organise Belgium as a Confederal State, which is also the best option for the leader of Catalonia’s Unió Democràtica Duran i Lleida.

A Confederal State is sort of an independence movement which does not say his name, formed by de facto independent States that retain their full sovereignty and can freely abandon the Confederation. If Belgium becomes one, Flanders manages to stay in the EU and be a sovereign State. It may leave Belgium whenever it wants and remain a member State since it already belonged to it as a sovereign State within a confederal State. Belgium is the Trojan horse of the independent movements in Europe.

OTHER CASES

As Germany’s Bavarian Finance Minister Markus Söder says: “The more successful we are, the more we must pay. It is like a punishment and the opposite of solidarity.” In Bavaria people feel German.

La Repubblica di Venezia was independent for more than 1,000 years. Now some want it to be independent again. The region shares a history and a dialect different from the rest of Italy’s. According to a survey 80% of the Venetians would support independence. Italy has also other nationalist fronts open in Sardinia, Alto Adigio or Tyrol from the South and especially the Padania. Since the 1970s a group of nationalists dream of creating a Federation in the North of Italy, leaving the poor South of the country and become one of the richest countries in the continent. According to a 2011 survey in the North of Italy 30% of the people supported full independence.

France is also hiding a puzzle of nationalisms behind its central State facade. Alsatian, Basque, Catalan, Breton, regulated, Occitan, flamingos… they all live with the idea of citizenship and equal rights under the umbrella of the omnipresent culture and French language. Only for that France is the most successful modern State thanks to the Revolution.

But future peace is not guaranteed if other European regions become independent states. In some cases tensions are already a fact. Nationalism is very present in French Britanny. And in Corsica, an independent Republic at the end of the 18th century incorporated by force to France although it kept a culture and a language closer to Italian, perhaps for being an island. There the separatist claim has always been strong. The nationalist parties remain with 25% of the votes and the Corsica Front of Liberation, a nationalist armed wing, is still active.

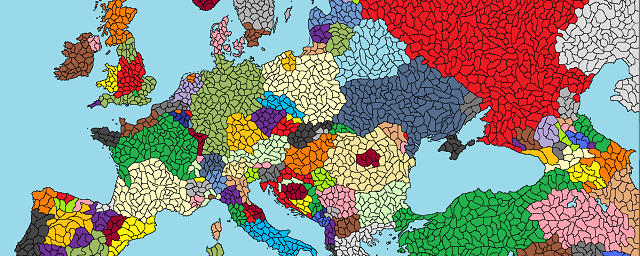

REBUILDING BORDERS

Europe’s borders have deeply changed in the last half-century, but peaceful changes as the Czechoslovak have been an exception. The most common case are the Balkans’.

The EU just won the Nobel Prize precisely for having achieved this fragile peace where there never was one. Its success against nationalism for more than half a century has been to promise a future without frontiers. But this has also become the antidote against the organization. Under the European peace umbrella we have the impression that it is possible to redesign those same borders prone to disappear without any risk. Fifty years of European construction have worn national states.

Madrid or London are not benchmarks anymore; Brussels is where most of the decisions are made. Secession seems less risky than before thanks to the democratic commitment of the Member States and to the economies of scale that the EU guarantees.

No matter how small a region, if there is common currency, a 500 million people market and a series of rights protected by EU institutions. The key to these nationalisms is to minimize the risks–real and clear ones–of them getting out of the EU, even in an agreed exit. Member States still retain most of the power through institutions.

In fact, if Member States feel in danger in the midway of European construction, they will stop participating the process. And then there will be the Europe of States, an intergovernmental Europe, not the federal Europe as some dream of.

Be the first to comment on "Integration and disintegration of the EU"