In a recent post, Scott Sumner replied to Paul Krugman’s take on market monetarists. Scott had something like 15 points but I’ll reproduce only 3:

“1. The Fed should not give monetary stimulus a try; they should do it.

“2. We don’t favor the same monetary policy. If we did they wouldn’t favor fiscal stimulus.

“5. The failure of monetary policy is partly bad motives (Rick Perry, etc) and partly ignorance. I find it hard to believe that ignorance isn’t the biggest part. I really can’t see how the entire western world would have created this needless catastrophe if they had know from the very beginning that the Fed and ECB could have easily prevented it, without running up debt (indeed shrinking deficits) and without high inflation. Why don’t people understand that monetary policy could have prevented this? When I talked to liberal intellectuals in 2008 and 2009 they almost all told me that we needed fiscal stimulus, because the Fed was out of ammunition. When I asked them where they got that crazy idea, roughly 100% cited a certain famous Nobel-prize-winning public intellectual.

“Yes, they misread his message to some extent, but then didn’t Mr. Krugman recently blame Rogoff and Reinhart for not working hard enough to prevent their message from being misinterpreted?”

In a later post, Krugman comments on a post by DeLong: “He’s referring to calls for the Fed and other central banks to raise expectations of future inflation as a way to get some traction in a liquidity trap — which is certainly something I and others support. But there are two crucial differences between us and the expansionary austerity types.

“First, our expectations argument is a hope; theirs is a plan. I want the Fed, the Bank of Japan, etc. to target higher inflation, in the hope that it might help, but it’s a hope, and meanwhile we need to fight demands for fiscal austerity and even push for stimulus. The expansionary austerity types, on the other hand, are (or were) actually counting on the supposed rise in confidence to avoid what would otherwise be nasty recessions, which have in fact materialized.

“Which brings us to the second point: those of us hoping to summon the expectations imp want to do so with policies that are at worst harmless, such as expanding the monetary base under conditions where this has no direct inflationary impact. The austerians, on the other hand, have pushed directly destructive policies — fiscal contraction in depressed economies — in order to achieve their hoped-for shift in expectations.

“So this is the difference between ‘Let’s try this possibly ineffective remedy, it might work and in any case won’t do any harm’ and ‘Let’s do the opposite of what standard analysis says we should be doing, just trust me.’

So you see, Krugman barely pays lip service to monetary policy. It’s only a hope and likely ineffective, so why bother?

Krugman bashes the austerians, and vice-versa, because their respective agendas are diametrically opposed. The market monetarist’s don’t have a political agenda behind their arguments, but if their proposals were tried and succeeded, they would prove Krugman wrong in saying that without fiscal stimulus (more government) the economy would remain subdued. In order to discourage something like Nominal GDP level targeting to be even tried, Krugman says it’s like ‘chasing rainbows’, or an ‘impossible dream’.

I’ll try myself to show that it isn’t an ‘impossible dream’. In doing so, I’ll argue that neither ‘fiscal austerity’ implies at all times a drop in economic activity or that ‘fiscal stimulus’ implies a strengthening in the economy’s performance.

In its closing, we’ll see that it’s monetary policy, the stance of which is measured by the level of NGDP relative to trend, that is vital for macroeconomic stability.

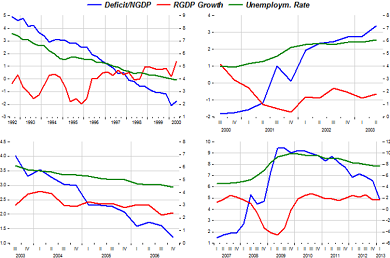

As measure of real economic performance I use the growth rate of Real GDP and unemployment. To measure the stance of fiscal policy I use the raw (not the cyclically adjusted) Federal Government deficit to NGDP ratio,

The set of charts that follow show fiscal stimulus/austerity, RGDP growth and the unemployment rate for distinct but successive periods over the last 20 years.

The two periods on the left hand side depict periods during which there was ‘austerity’ (declining deficit/increasing surplus). Note that during those episodes growth picked up and unemployment fell.

The two periods on the right hand side illustrate periods during which there was fiscal stimulus (rising deficit/declining surplus). During those times growth faltered and unemployment rose. Note that in the recent cycle, after becoming significantly negative despite the strong rise in the deficit, growth picks up, and unemployment falls somewhat when fiscal ‘expansion’ turns to ‘austerity’. But as we’ll see, that’s not because there was ‘more austerity’.

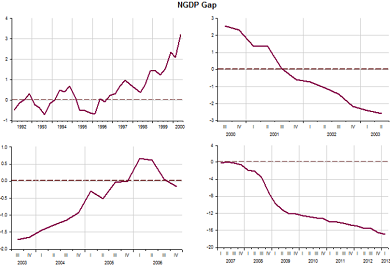

As the next charts for the exact same periods show, higher (or rising) growth and falling unemployment are closely associated with what’s happening to monetary policy (‘expansionary’ if NGDP is above (growing more) than trend and ‘contractionary’ if NGDP is below (growing less) than trend.

So monetary policy is not an ‘impossible dream’. In the more recent episode, even though the ‘NGDP gap’ is still widening, it is doing so at a lower ‘speed’, indicating that although monetary policy is still contractionary, after mid-2009 it has become less so. Note that that was enough to reverse the real growth and unemployment trend, despite ‘fiscal austerity’ kicking in. Just imagine what would have been if monetary policy had been ‘explicitly expansionary’!

Interesting, but it is clear that the US is growing and the EU is stuck. Dont you think that, all in all, the major difference has been on monetary policy? General ideas are simplistic, but help to set the direction. It is not that austerity is all bad or that expansion is all good, but it seems the first is worst than the second.